The murder of a Lower East Side teenager this past weekend has, understandably, shaken a lot of people who live in, or have ties to, the neighborhood’s public housing developments. For now, friends and family are focused on tomorrow’s funeral of 18-year old Keith Salgado. But when the mourning is over, Salgado’s killing Saturday night at the Campos Plaza complex, three blocks from his home on East 9th Street, is sure to renew an all-too-familiar debate about youth violence in this community.

In the three precincts that make up the Lower East Side, there have been five murders so far this year (not including the Salgado case). Compared with the bad ol’ days, (60 murders were recorded in 1990), the statistics don’t seem so alarming. But lots of people believe the numbers (which have always been suspect) don’t come close to telling the whole story.

The neighborhood has seen its share of high profile violent crime in the past couple of years. In June, a 21-year old man was fatally shot on Pitt Street. Police suspect the crime was related to drugs and gangs, but no arrest has been made. In February, longtime LES resident Jomali Morales was killed at the Baruch Houses; a 19-year old man will soon go on trial for her brutal stabbing. And two years ago, 21-year old Glenn Wright was fatally stabbed, also at the Baruch Houses, in an apparent case of mistaken identity. Many other smaller incidents go largely unreported. Just this week, shots were fired on Rivington Street, leading to a major show of force by the 7th Precinct.

For us, telling the neighborhood crime story (beyond the headlines) has not been easy. For obvious reasons, no one is very anxious to talk on the record. But several weeks ago, three youth counselors who grew up on the LES and have a lot of experience working with at-risk kids, agreed to sit down with us for a candid conversation. They talked on the condition that their names and the program they work for be kept out of the story.

The counselors have the respect of the kids they work with because they’re “of the neighborhood.” They’ve walked in their shoes, personally confronted many of the same problems and continue to live in the community.

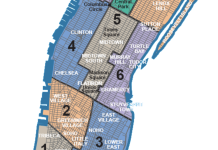

The first thing that needs to be understood, they told me, is that this neighborhood is deeply divided. Kids strongly identify with the housing projects in which they live. Rivalries among the different developments are intense, and local gangs are a major factor in all of them. They talk about different sections of the Lower East Side as though they’re really separate neighborhoods. There’s “The Ave,” as in Avenue D, where the Wald and Riis Houses are located. “The Hill” is made up of the developments south of Houston, including the Vladeck, LaGuardia, Rutgers and Smith Houses. The Baruch Houses are thought of as “the middle ground” between the two main areas.

The counselors said a lot of kids fear traveling back and forth between different parts of the neighborhood. “I think for awhile it was changing for the better,” one of them explained. “You could cross neighborhoods safer. I think now we’re sort of regressing for some reason. We’re like going back into the 80’s.” Maybe it’s the economic downturn, or something else. But the bottom line, they said, is that tensions are rising:

We have a young man. He gets jumped repeatedly. He cannot step outside the (edited to remove specific location) area. The swimming pool that all the kids go to is on Pitt Street. He can’t go there because he has to go by the Baruch projects. He comes and lets us know he’s getting jumped. If you can’t cross the street because there’s someone from a different project waiting for you, that’s a problem.

Even as gentrification has taken hold, there’s a sense in some parts of the neighborhood that time is standing still. People talk about the city’s notorious anti-crime sweeps of “Alphabet City” 20 years ago, as though it was just the other day. In some ways, we were were told, very little has changed:

In the early 90’s, especially on The Ave, they did a huge sweep. Everybody got arrested. Now they’re all coming out of jail. Or their kids are now teenagers and all they know is the street life, the drug life. So they try to follow in their footsteps. And the ones coming out of jail, because they have no other skills, go back into “the street system.” There are no options when you come back, so all you can do is come back to what you know. There’s no re-introduction into society. You got discharged. Someone picks you up and the second you’re out, you’re pacing all your old stomping grounds… They’re selling weed and they’re all in competition for the same clients because no one from this neighborhood leaves this neighborhood. All of the parents here are from the crack cocaine-dope era. So half of (the kids) are products of drug users — their community is completely built on that. This is what they know. This is what they’ve been taught.

The trio we spoke with said they try to show the kids there are better options:

It’s about exposing them to a different lifestyle, introducing them to culture, showing them that Manhattan goes beyond 12th Street. It doesn’t stop at Houston… For us, it’s not about changing a life. It’s about — how can you process a thought in this young person’s mind to at least give them the option to think beyond what they know?

One of the challenges, they said, is that most of the college readiness programs (SAT classes, college application counseling, etc.) are located on “The Hill.” Since teens from Avenue D are reluctant to cross Houston Street, they’re cut off from the kind of aid that could lift them out of “the hood.”

[Others in the neighborhood’s human services community downplay the idea that kids interested in college prep programs are unable to travel from one part of the LES to another. The real problem, they suggest, is that the drug trade on Avenue D provides kids with easy money, and very little motivation to seek other opportunities.]

The more fundamental issue, the counselors argued, is that no one – not the police department, not the political establishment – wants to admit there’s a problem. In public forums and during interviews, NYPD officials have rejected the notion that well-organized drug gangs are operating on the Lower East Side. Instead, they have suggested, violent incidents are the result of localized feuds among a few “bad kids.”

I asked the three youth counselors what they thought of this argument:

Isn’t it a problem if police are only identifying large gangs and not the local group if they are involved in all kinds of activities that are not legal, whether it be with gun play, whether it be with drugs? If the focus is just on Bloods because they’re more well known, what happens to groups like (gang names removed)? If they continue to turn a blind eye to what happens it’s going to continue to fester. You can’t put a band-aid on an open wound. That is just not realistic.. A lot of crime is not reported. We see it. We get the texts. We talk to the kids. We see their Facebook posts. Other People are not seeing it because they’re seeing what they want to see.

So what would make a difference? I asked what they’d tell the neighborhood’s elected officials and community leaders if given the opportunity:

I need people to give a shit. I need politicians to get off their ass and come down here at 10 o’clock, 11 o’clock, 1 o’clock in the morning and see what’s going on. I need all of these community leaders to stop glorifying all the good and take a realistic look at what’s happening in this neighborhood. We are not the East Village. We are the Lower East Side. I need people to start volunteering and giving back to their neighborhood. Don’t just come here for a photo op. Come here to help. And tell everyone in your office to help, too. Become a mentor. Implement some kind of program you will be proud of.

There’s definitely a need for more youth programs, especially above Houston Street, they said, but also programs to help families improve their economic situations:

Our parents need a lot of help. We may have the kids for 4 or 5 or 6 hours. But the parents have them the rest of the time. If these parents are not feeling good about themselves, or do not have the resources they need because they don’t have the education or they can’t find a job and they’re out there selling drugs or whatever they gotta do, everything we just did with a kid for three hours just goes out the window. It goes out the window the minute they walk in that door at home and your mom is smoking weed or your dad is doing crack. So in order to help the kids we have to have programs that support the parents. Parents are not involved in their childrens’ lives. It’s very hard to get them involved, especially for the teenagers. At 15 or 16 you had to fend for yourself. You can’t blame the parents because they’re doing what they know.

In the aftermath of Keith Salgado’s murder, more than a few people were heard declaring the time had come to “get out of the hood.” But at least one of the youth counselors said leaving the community is not the answer:

I think that’s the mentality that’s been pushed on everyone. They say “I want to do good so I can get out of here.” Why? Why can’t you do good so you can stay here and keep helping the neighborhood. Go to college, and then come back and make the hood better.

At the same time, the current environment is obviously far less than ideal. As one of the counselors put it, “We don’t live in this community. We survive it.”